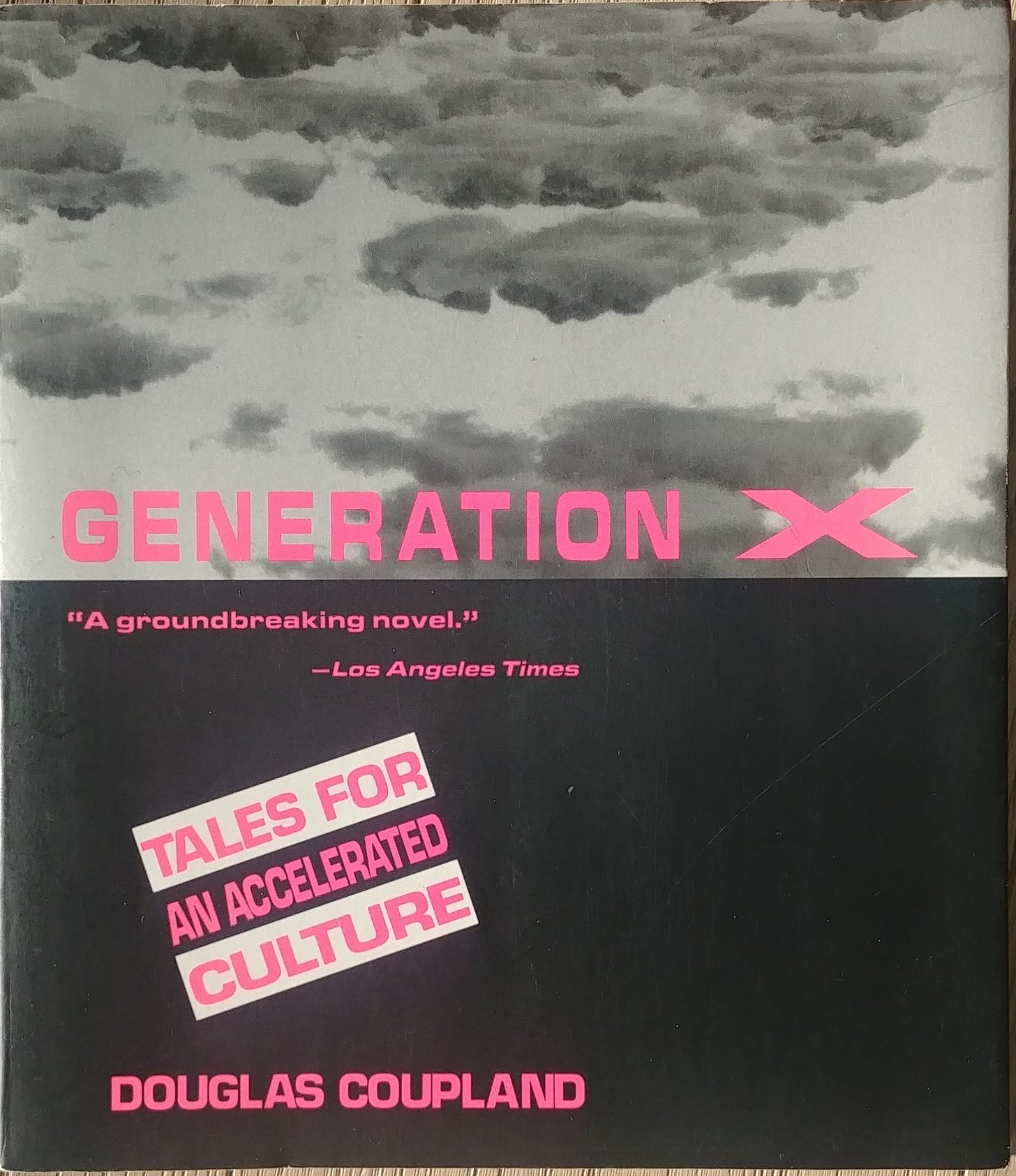

Generation X:

Tales for an Accelerated Culture by Douglas Coupland

When I first read Generation X: tales for an accelerated culture by Douglas Coupland in 1991, I felt as if his characters were just like me and my friends, having similar conversations, expressing our important concerns, sorting through where we stood on our ideas and beliefs. As I read the book again, it refreshes memories of my friends that were philosophical about the meaning of our existence as we were making life decisions, transitioning from being university students into becoming adults. We shared despondency about our career prospects, uncertainty for what the future held. We wanted to make choices that were beyond the status quo, yet we did not know exactly what those choices could be.

With each re-reading, I reminisce about how the book, Generation X, gave a voice to what my generation was experiencing as we came of age, and how the book’s ideas, opinions and world view captured what was important to me both then and now. Not always overt, not always top of mind, but when crisis happens, these Gen X themes emerge for me again.

I have a renewed sense of wanting to become and sustain a different perspective than the status quo, to consciously choose a unique path forward. I want to look objectively at what is presented, to make a fair assessment of the current situation, and self-determine how I want to be. I make time to mull over what brought me here, see with fresh eyes to select distinctive options, and importantly, to be able to explain to myself and others why I am beginning again with a new starting point.

Unlike thirty years ago, when that new starting point felt remarkable and rare, this time, I can also predict with comfort and confidence that the new starting point is more likely a refreshed version of my usual patterns. With that clarity in place, I can expand my search for the thrill and excitement of starting something new to be less about learning again about my known patterns, and instead see aspects that have been unavailable due to distractions and resistance.

Generation X reminds me that sometimes the more we change, the more we stay the same. I give credit to Coupland for explaining and characterizing my rites of passage into adult life during and after university. I embodied the existential angst of the uncertainty of starting a career in the shadow of the baby boomers. I wanted to know more about global cultures, other options for ways of living, and not commit myself to a path that seemed well travelled by our parents. Impermanence by way of travel, was a statement of my refusal to commit. During the 1990s, it was a good time to be nomadic. The constant moves, starting again with temporary jobs, new people, new places were symbols of freedom and being unburdened. As Tragically Hip sung, “I have a job. I explore. I follow every little whim.”

Overall, there were only a few examples of danger, as I pushed my boundaries to their maximum. I avoided disaster at the time, and in hindsight, I shudder at the ‘what if that had gone awry’ memories. Ultimately, it became exhausting to sustain being nomadic and alone indefinitely. Perhaps, I had had enough of near misses. Something hinted, I was bound to run out of lucky stars. Doubt crept in. In my mid-30s, I made the decision, tired and road-weary, to move to a big city, where there were well-paying jobs. Just when I had earned enough to fund a backpacking trip through Europe, I met a man whom I married three years later. With marriage came homeowning, and our lives as career professionals anchored us. Changing my direction, yet again.

I have been telling my story about the peak of my career as a burn out story. I peaked – it was great, and then I crashed, and then crashed again. The story of the devastation of the crash has come to overshadow the joys and thrills of the peak. There are aspects of the journey to the peak that I do miss. I want to balance some of the call of adventure, with wisdom of not going too far with it. Looking back, I yearn for the exuberance of being 'on' and being ‘all in’ - juggling multiple high stakes initiatives that need my attention, my skillset, my expertise. I learned the hard way that the adrenaline and cortisol that runs through the body is harmful if overused. Yet, those hormone surges sustained the thrill, and were, I think, necessary to be able to accomplish all the work. I ask, on the other side of menopause, are there other ways to energize, motivate and push through? I seek ways to include compassion and empathy for self in hindsight. I have different assumptions about prestige and competitiveness, reminding myself that I have other options beyond struggling with power.

With this re-reading of Generation X, I had a revelation. Instead of focusing on the really low points of my burnout, and yearning to find a comparable replacement for the high points, I am interested to explore the turning points, the choices made at everyday crossroads. Not the life or death decisions of the high stakes, but the regular, yet significant choices that are presented to us all the time – do we engage with action or not, do we block it from our minds or not, do we go alone or with others - that are a reminder of what we count on for our personal truths. One of the main themes of Generation X that I had lost track of was that we need to, we get to, choose how we assign meaning as we make our way.

It's a bold statement to say that a book has the power to give me courage to set a direction in life. But I will say it here as I confirmed my own beginnings with a recent tourist trip to Japan; I went back to where I had started my adult years, thirty-four years ago. In the early 1990s, a Gen X’s job option was to teach conversational English abroad. I wanted to experience the world beyond what I know locally; in my 20s and 30s it meant travel. I continue to study art history and literature of different cultures; Japan opened my eyes to Buddhism and Eastern wisdom teachings. I have spent my adulthood learning about myself in the context of other people, both friends and enemies, through their stories of how things are, their teaching about life lessons.

We assign meaning as we make our way

There have been a few friendships in my life where I share the delight that Andrew has when he meets Claire and ‘was in heaven! How could [he] not be, after finding someone who likes to talk like this’ (p.37) – and the premise of their friendships and the novel, ‘to tell stories and make our own lives worthwhile tales in the process’ (p.8) As they reflect upon their mid-twenties breakdowns, there is a comparison to my Gen X friends as we approach our 60s, and are exploring what is next, as we enter into what I call post-adulting. We are less worried about careers and finances, parenting young children, homemaking, and instead are navigating the empty nest feeling of what is to be next. We are regrouping on what makes our lives worthwhile in the telling.

It wasn’t all a disaster, but what pains me the most is the loss of autonomy

My career burnout represents a loss of autonomy, where my choices were perceived to be limited, and the consequences were heavily weighted with the fear of what others would think. I stayed too long, was too far off track and lost my vision, which resulted in bitterness and emptiness. Generally, rationally, there were other legitimate reasons for the situation, it wasn’t all a disaster, but what pains me the most is the loss of autonomy. And yes, of course, I did choose all my own actions, and as I reflect upon how I behaved to others while under duress, I do have evidence that I maintained my composure. The struggle was internal. The cost was my self-confidence; I had allowed myself to become small, restricted, trapped. A recurring thought was to insist ‘I can do better than this’ and the turning point happened when the next thought was to ask ‘do I want to.’ A resounding ‘no’ opened a door to explore new choices and different friendships.

The cautionary tales from naysayers and worriers, and that I also adopted during my burnout decade, echo what Coupland laid out in his story of Andrew, Dag and Claire. How the coming-of-age characters sort out what matters most, how they will symbolize this importance with their choices and actions, the secondary characters that provide clear examples of what they want to avoid, and the stories within the story that narrate their viewpoints on their fears and desires still resonate each time I re-read the novel. It makes me think about my ongoing debate over the importance of finishing what you start and taking pride in quality workmanship as compared to doing what it takes to follow your dreams, to be true to your self, and to not stagnate in a non-dream situation. The mainstream of consumerism as set out by our parents’ generation and society at large, is to be avoided. We take pride in making the significant trade-offs, as we make choices about how and what we consciously participate in.

There is an unanswered question of what will Andrew, Dag, and Claire do next as the story ends with a new adventure that is left vague and unclear. I appreciate the ending more these days. It would be nice to drop out, walk away to seek out the next frontier, farther away from the woes of society and begin again.

What does it take to not be influenced by someone else’s agenda, to not be duped into believing I am not enough, and to take a stand that I am living my own life, following my own conscious decisions to their logical outcomes. I remind myself that my current situation has endless options, some more appealing than others, but always I can make a choice for what I do next, what I say to others, and what I think about myself for living as fully as I can.